In the realm of energy and space exploration, a team of researchers from various institutions, including the University of Chicago, the University of California, Santa Cruz, and the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, have been working on a novel approach to detect dark matter using advanced sensor technology. Their work, published in the Journal of Instrumentation, focuses on the Dark matter Nanosatellite Equipped with Skipper Sensors (DarkNESS) mission, which aims to search for X-ray lines from decaying dark matter using Skipper-CCDs.

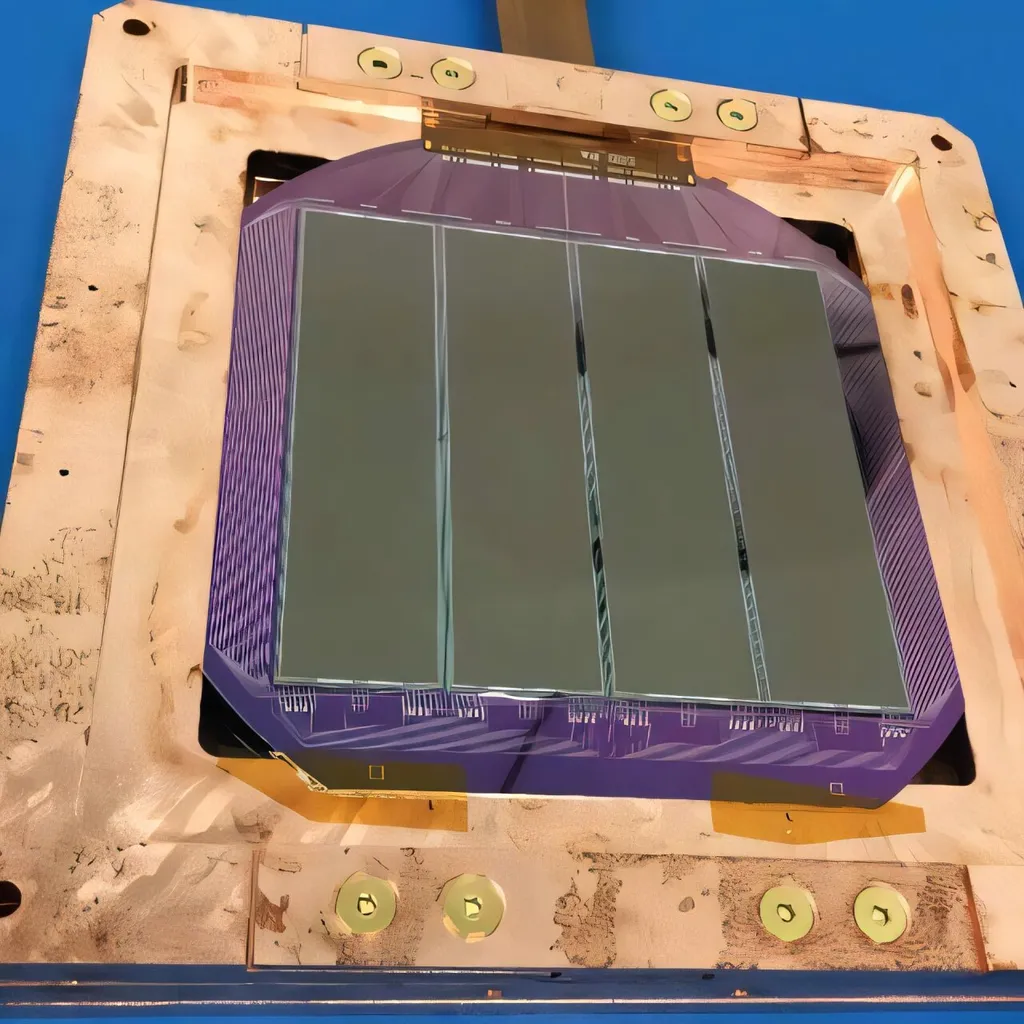

The DarkNESS mission utilizes a 6U CubeSat, a type of miniaturized satellite, equipped with thick, fully-depleted p-channel Skipper-CCDs. These sensors are designed to provide low readout noise and high quantum efficiency for X-rays in the 1-10 keV range. However, their performance in the space environment, particularly under radiation exposure, has not been thoroughly demonstrated until now.

The researchers exposed a Skipper-CCD sensor to 217 MeV protons at a fluence of 8.4 x 10^10 protons per square centimeter. This level of exposure is significantly higher than what the sensor would experience over a three-year period in representative low-Earth orbits, including mid-inclination and Sun-synchronous orbits. The purpose of this extreme exposure was to simulate the worst-case scenario for radiation damage and to assess the sensor’s performance under such conditions.

Using a 55Fe X-ray source, the team compared the energy resolution of the irradiated sensor quadrant to adjacent unexposed quadrants and a non-irradiated reference sensor. The results provided a quantitative assessment of the radiation-induced spectral degradation in Skipper-CCDs. The researchers found that the proton irradiation increased charge-transfer inefficiency, which in turn degraded the X-ray energy resolution. However, the sensors still maintained a high level of performance, indicating their potential for use in space-based X-ray detection missions.

The practical applications of this research for the energy sector are primarily indirect. While the primary goal of the DarkNESS mission is to detect dark matter, the development of radiation-hardened sensors with high energy resolution has broader implications. For instance, such sensors could be used in space-based solar power systems to monitor and characterize the solar wind and other space weather phenomena. Additionally, the technology could be adapted for use in terrestrial applications, such as nuclear power plants, where radiation-hardened sensors are crucial for monitoring and safety systems.

In conclusion, the research conducted by Phoenix Alpine and colleagues represents a significant step forward in the development of advanced sensor technology for space-based applications. While the immediate focus is on dark matter detection, the potential applications for the energy sector are promising and could contribute to the development of more robust and reliable monitoring systems in both space and terrestrial environments. The research was published in the Journal of Instrumentation, providing a valuable resource for scientists and engineers working in related fields.

This article is based on research available at arXiv.