In the realm of energy journalism, it’s not often that we delve into the world of conflict dynamics. However, a recent study by researchers Moussa Abdou and Neil F. Johnson from the University of Miami offers insights that could have significant implications for the energy sector, particularly in regions like Yemen and Syria. These areas are not only hotspots for conflict but also critical regions for global energy resources.

Abdou and Johnson’s research, published in the journal Nature Human Behaviour, focuses on understanding the patterns in conflict dynamics. They found that conflict fatalities tend to follow heavy-tailed statistical distributions, a phenomenon predicted by a 2005 fusion-fission theory. This theory suggests that for armed groups operating in dynamically evolving clusters within a given conflict, the number of fatalities per conflict event will follow an approximate power-law distribution with an exponent near 2.5. The specific exponent value offers insight into the relative robustness of larger versus smaller clusters of fighters in that armed group.

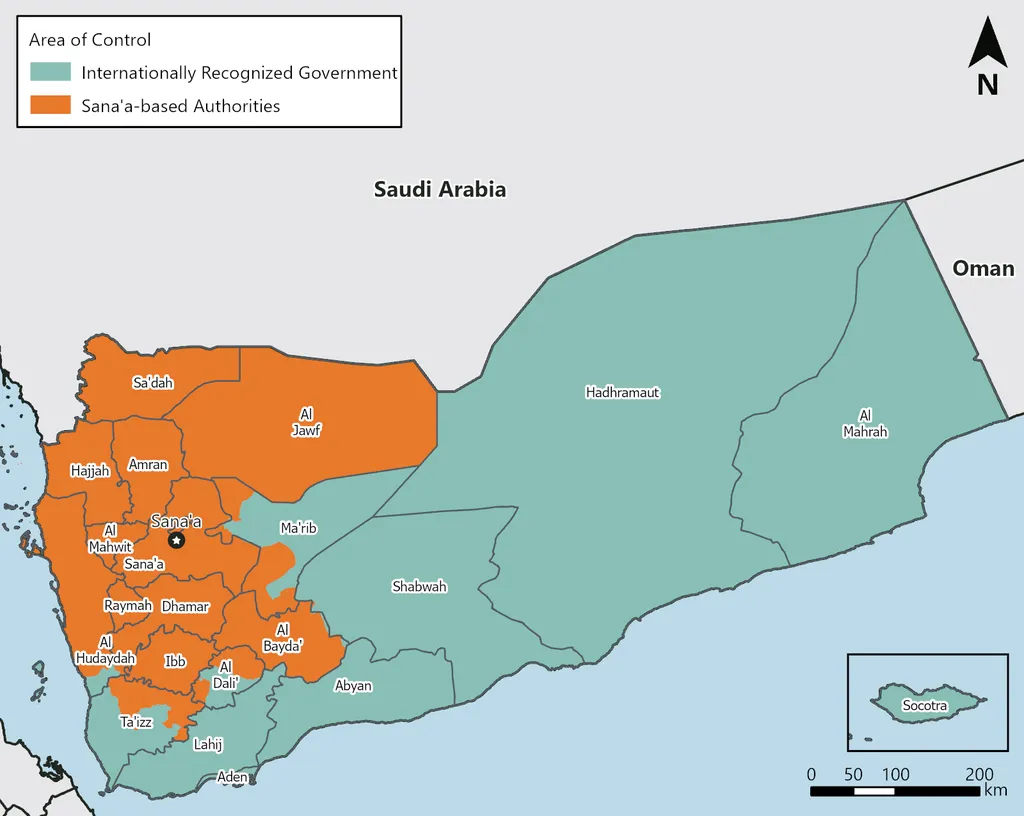

The researchers used data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) to determine the best-fit exponent value for the recent conflicts in Yemen and Syria (2023-2025). They found that the exponent lies between 2.5 and 3.5 predominantly throughout each conflict. This suggests that the fighters in each of these conflicts continued to operate in smaller clusters as the conflict evolved.

Interestingly, the researchers also noted temporary reductions in the exponent value, which suggests a temporary increase in the robustness and involvement of larger clusters of fighters. These reductions appear to arise during major crises ahead of the largest battles. While the lack of higher-quality data prevents the researchers from establishing this more firmly, such a temporary reduction in the exponent value hints at its potential use as an early-warning signature.

For the energy sector, understanding these patterns can be crucial. Energy infrastructure, such as oil and gas pipelines, refineries, and power plants, are often targets during conflicts. By predicting the dynamics of these conflicts, energy companies can better prepare and protect their assets. Moreover, understanding the robustness of different clusters of fighters can help in assessing the risk of attacks and planning mitigation strategies.

In conclusion, while the energy sector may not be directly involved in conflict resolution, understanding the dynamics of conflicts can provide valuable insights for risk assessment and mitigation. The research by Abdou and Johnson offers a promising avenue for predicting conflict patterns, which can be invaluable for energy companies operating in high-risk regions.

This article is based on research available at arXiv.