As the world grapples with the urgent need to transition to sustainable energy sources, nuclear power is regaining attention, even in countries like Sweden that had previously shied away from expanding their nuclear capabilities. The recent announcement by state-owned energy company Vattenfall to explore the deployment of small modular reactors (SMRs) at the Värö Peninsula marks a significant shift in Sweden’s energy strategy. However, this pivot towards nuclear power is not without its complexities, particularly concerning nuclear non-proliferation.

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) has long emphasized the importance of proliferation resistance in nuclear energy systems. This concept is particularly relevant for new technologies like SMRs, which can introduce novel aspects into a country’s nuclear fuel cycle, potentially increasing proliferation risks. For Sweden, this could mean grappling with new challenges such as load-following reactors, cogeneration of district heating, hydrogen production, and dry storage of used nuclear fuel, all of which could influence proliferation risks in ways that are not yet fully understood.

A recent study conducted within the ANItA competence centre has sought to address these concerns by conducting a proliferation resistance assessment of Sweden’s potential SMR deployment using the IAEA’s INPRO methodology. The assessment focuses on three key requirements: the adequacy of the state’s legal framework on non-proliferation, the low attractiveness of nuclear technology and material, and the facilitation of IAEA nuclear safeguards through system design.

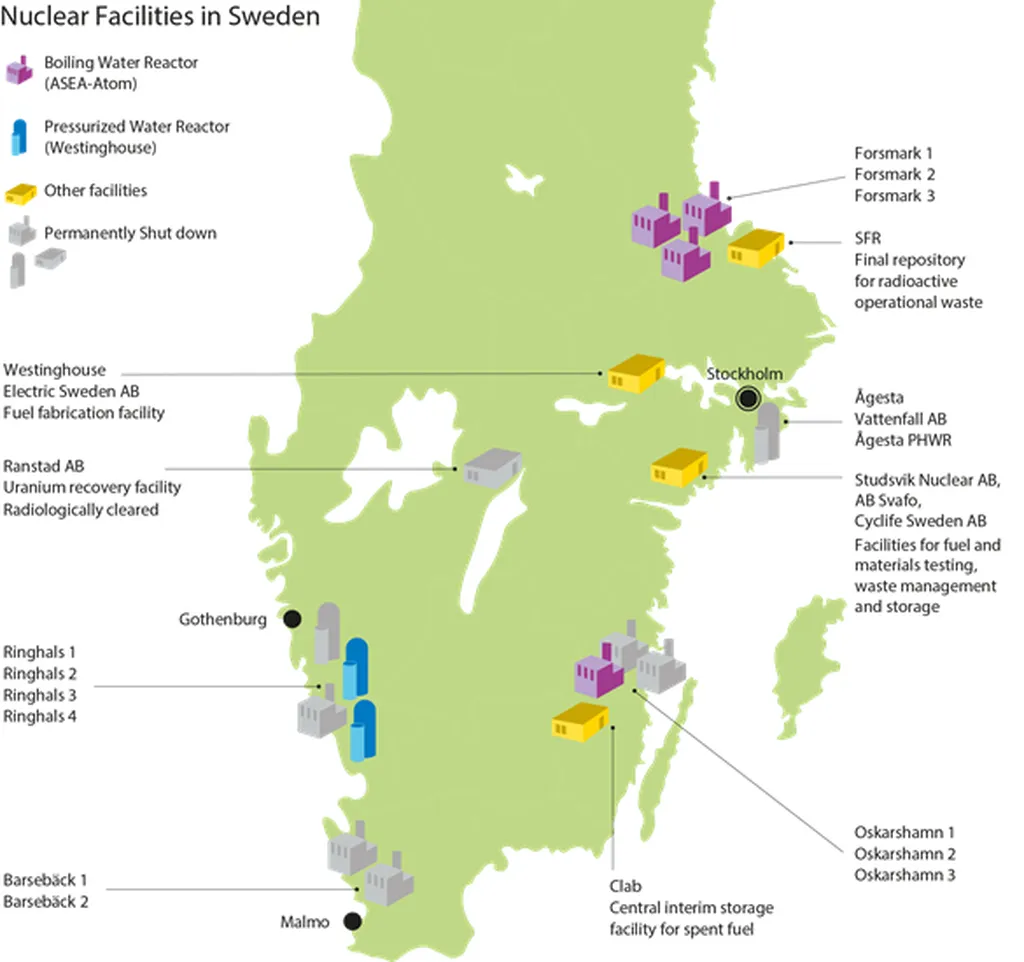

The study considers a hypothetical scenario involving the deployment of three light water SMR units and a dry intermediate storage facility at the Forsmark nuclear site. This scenario is designed to mirror Vattenfall’s plans for the Ringhals nuclear site and takes into account the current nuclear waste management solutions licensed for the operating reactors.

The findings of this assessment could have significant implications for the future of nuclear power deployment in Sweden and beyond. If the assessment identifies areas where proliferation risks are heightened, it could prompt early coordination and design choices that ensure new technologies remain unattractive for weapons development. This could involve the adoption of intrinsic design features that make nuclear material less suitable for weapons, as well as the implementation of extrinsic measures like enhanced safeguards and inspections.

Moreover, the study highlights the importance of early dialogue between stakeholders, including facility owners, operators, designers, constructors, national safeguards regulators, and the research community. This collaborative approach, known as Safeguards by Design (SbD), can help integrate international safeguards considerations into the design, planning, construction, operation, and decommissioning of nuclear facilities. The SbD process is officially supported by Euratom and the IAEA, underscoring the global recognition of its importance in ensuring the peaceful use of nuclear technology.

As Sweden moves forward with its plans to deploy new nuclear reactors, the insights gained from this proliferation resistance assessment will be crucial. They will not only shape the development of Sweden’s nuclear energy system but also contribute to the broader global discourse on how to balance the need for sustainable energy with the imperative of nuclear non-proliferation. The study serves as a reminder that the path to a sustainable energy future is complex and requires careful consideration of all potential risks and benefits.