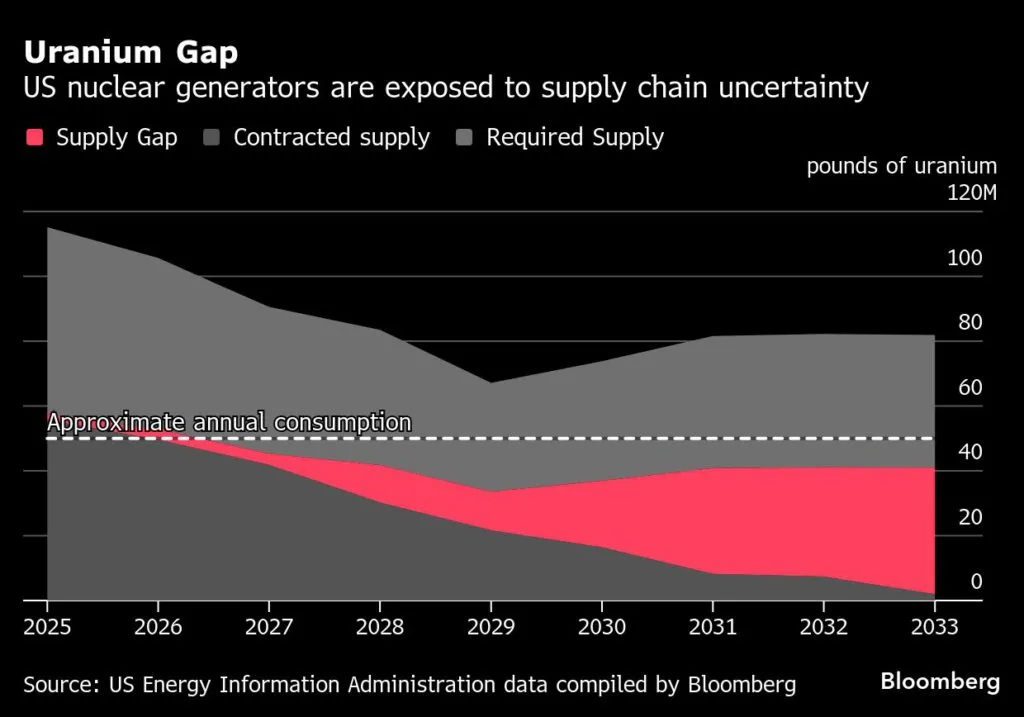

The United States’ ambitious plans to expand nuclear power to meet surging electricity demand are encountering an unexpected hurdle: uranium fuel. While policy momentum and private investment are pouring into both existing plants and next-generation reactors, the supply chain that delivers uranium fuel is strained, geopolitically exposed, and slow to scale. Recent industry discussions underscore that without swift action, fuel availability could limit the pace and security of America’s nuclear power growth.

Rising electricity demand, driven by the proliferation of energy-intensive AI data centers, the reshoring of manufacturing, and the electrification of transportation and buildings, has positioned nuclear energy as a key solution. Nuclear’s low-carbon footprint and consistent output make it an attractive option. However, expanding nuclear power isn’t just about building reactors—it also requires a robust supply of uranium fuel, which recent analyses suggest is far from guaranteed.

Over 100 leaders from the nuclear fuel sector, including utility executives, reactor designers, government regulators, and industry experts, convened in Arlington, Virginia, for the Nuclear Fuel Cycle Roundtable. Organized by Stanford University’s STEER initiative, part of the Precourt Institute for Energy and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, the meeting examined barriers to uranium fuel production and explored strategies to strengthen the supply chain. The findings highlight both immediate and long-term challenges for uranium fuel.

The roundtable emphasized that while investment interest in nuclear reactors is high, fuel supply constraints could undermine these ambitions. Producing uranium fuel involves four major steps: mining uranium ore, converting it into a gaseous form for enrichment, increasing the concentration of fissile U-235, and fabricating fuel rods for reactors. Each stage presents vulnerabilities.

Mining is dominated by four countries: Kazakhstan, Namibia, Australia, and Canada. The U.S. produces only a small fraction due to higher costs and lower-grade ore. While mining risks are mitigated by friendly partners, reliance on foreign sources creates strategic exposure. Kazakhstan, the largest producer, is also pursuing autonomy from Russia and China, creating potential opportunities for U.S. engagement.

Conversion is another bottleneck. Only five facilities worldwide convert mined uranium into gas for enrichment. Market volatility has led to repeated shutdowns and capacity uncertainty, shrinking global stockpiles. Without long-term contracts guaranteeing demand, suppliers are reluctant to expand.

Enrichment presents significant geopolitical risks. Almost half of global enrichment capacity is in Russia. Before the U.S. ban on Russian uranium imports in 2024, about 30% of U.S.-enriched uranium came from Russia, highlighting a significant geopolitical risk. This concentration raises concerns over national security and long-term reliability.

Fabrication is the one area where the U.S. is self-sufficient, producing ceramic fuel pellets and assembling fuel rods. However, experts at the roundtable stressed that national and economic security would benefit from domestic capability across all supply chain stages.

Government initiatives are beginning to address these vulnerabilities. Recently, the Department of Energy awarded $2.7 billion in contracts to domestic enrichment companies for conventional and advanced reactors. These investments signal growing recognition of uranium fuel as a strategic priority. Yet challenges persist. Utilities are hesitant to commit to long-term fuel contracts at current high prices, while suppliers cannot justify new facilities without guaranteed demand. Roundtable participants suggested that government entities could act as buyers of last resort, ensuring revenue certainty and unlocking private investment.

Geopolitical uncertainty also complicates planning. Waivers or workarounds could weaken the effectiveness of the U.S. ban on Russian enriched uranium, and investors remain concerned about the long-term durability of such policies.

Next-generation reactors amplify fuel pressures. These reactors require higher levels of uranium enrichment, meaning each ton of fuel requires significantly more mined and processed uranium than conventional reactors. While advanced fuels produce electricity longer, initial demand could strain mining, conversion, and enrichment capacity, potentially driving up costs for existing reactors. New fuel forms also bring technical hurdles. Limited commercial experience and low initial fabrication yields could increase costs, while access to test reactors remains scarce. Currently, only one operating Gen IV reactor exists worldwide, in China. Standardizing fuel specifications and closer coordination between reactor designers and manufacturers could help accelerate the learning curve and reduce early inefficiencies.

The Nuclear Fuel Cycle Roundtable concluded that reducing technological, economic, and policy uncertainty is essential to secure uranium fuel for both conventional and advanced reactors. Key strategies include coordinating international partnerships and fuel standards, clarifying and enforcing geopolitical policies, including import bans, investing in research and development for cost-effective fuel manufacturing, and aligning public and private stakeholders to support long-term capacity expansion.

Uranium fuel, once a background concern, is now central to the success of the U.S. nuclear power renaissance. Ensuring a reliable supply is critical to expanding nuclear energy safely, affordably, and at the pace required to meet the country’s growing electricity needs.