In the realm of energy and technology, precise timekeeping is crucial for various applications, from power grid synchronization to data center operations. A team of researchers from the University of California, Berkeley, the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and the Russian Quantum Center has made significant strides in developing a temperature-insensitive composite diamond clock, as detailed in their study published in the journal Nature Communications.

The researchers, led by Sean Lourette and including Andrey Jarmola, Jabir Chathanathil, Victor M. Acosta, A. Glen Birdwell, Peter Blümler, Dmitry Budker, Sebastián C. Carrasco, Tony G. Ivanov, Shimon Kolkowitz, and Vladimir S. Malinovsky, have tackled a longstanding challenge in the field of solid-state clocks. These clocks, which use the spins of electrons and nuclei in solid materials to keep time, offer advantages such as compactness, robustness, and ease of integration. However, one major hurdle has been the sensitivity of these clocks to temperature fluctuations, which can lead to inaccuracies.

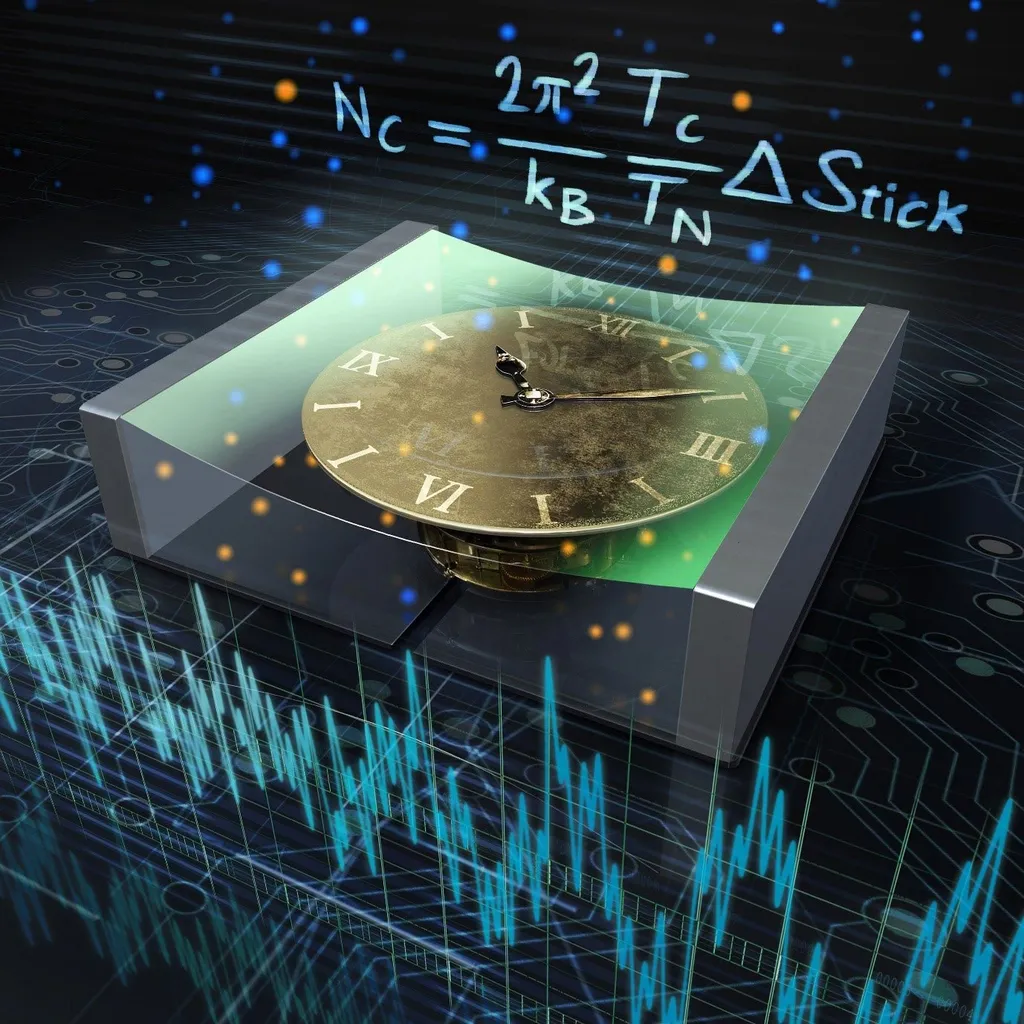

The team focused on nitrogen-vacancy (NV) centers in diamond, which are naturally occurring defects in the diamond lattice that can be used as a frequency reference. The electronic properties of these NV centers are highly sensitive to temperature changes, making them unsuitable for stable timekeeping on their own. To overcome this limitation, the researchers developed a composite frequency reference that combines measurements of the electronic splitting (D) with the nuclear quadrupole splitting (Q) of the nitrogen nucleus within the NV center. This composite approach allows for temperature compensation, resulting in a more stable clock.

To demonstrate the effectiveness of their method, the researchers implemented a specialized pulse sequence with an eight-phase control scheme. This sequence suppresses pulse imperfections and enables interleaved measurements of D and Q in a high-density NV ensemble. The stability of the composite diamond clock was then characterized over a 10-day period at room temperature, with comparisons made to a rubidium vapor-cell clock. The results showed a fractional instability below 5 x 10^-9 for an averaging time of 200 seconds and below 1 x 10^-8 at 2 x 10^5 seconds, representing improvements by factors of 4 and 200, respectively, over a clock based solely on the electronic splitting D.

Furthermore, the researchers investigated the residual sensitivity of the composite clock to magnetic fields, optical power, and radio-frequency drive amplitudes. They found that temperature was no longer the dominant source of instability, indicating the success of their temperature-compensation strategy.

The practical applications of this research for the energy sector are manifold. Accurate and stable timekeeping is essential for the synchronization of power grids, ensuring efficient and reliable energy distribution. Additionally, compact and robust solid-state clocks can be integrated into various energy systems, from smart grids to renewable energy installations, enhancing their performance and reliability. The development of temperature-insensitive composite diamond clocks represents a significant step forward in the field of frequency metrology, offering a viable route to thermally robust and multifunctional solid-state clocks and quantum sensors.

In conclusion, the work of Lourette and his colleagues provides a promising solution to the challenge of temperature sensitivity in solid-state clocks. Their composite diamond clock technology has the potential to revolutionize timekeeping in the energy sector, contributing to more efficient and reliable energy systems. The research was published in the journal Nature Communications, offering a detailed account of their findings and methodologies.

This article is based on research available at arXiv.