In the realm of energy journalism, it’s crucial to stay abreast of scientific research that could potentially impact the energy sector. Today, we delve into a study that explores the influence of the Parker spiral, a phenomenon related to the solar wind, on a process known as reflection-driven turbulence. This research could have implications for understanding and predicting space weather, which in turn affects satellite operations, power grids, and other energy infrastructure.

The study was conducted by Khurram Abbas and Jonathan Squire from the University of Otago in New Zealand. Their work, titled “The influence of Parker spiral on the reflection-driven turbulence,” was published in the journal Physical Review E.

The solar wind, a stream of charged particles released from the upper atmosphere of the Sun, is known to heat up as it travels through the heliosphere, the vast bubble-like region of space dominated by the solar wind. This heating is more significant than what would be expected from adiabatic cooling, a process where a substance cools down as it expands. The researchers propose that this additional heating could be due to a process called reflection-driven turbulence (RDT).

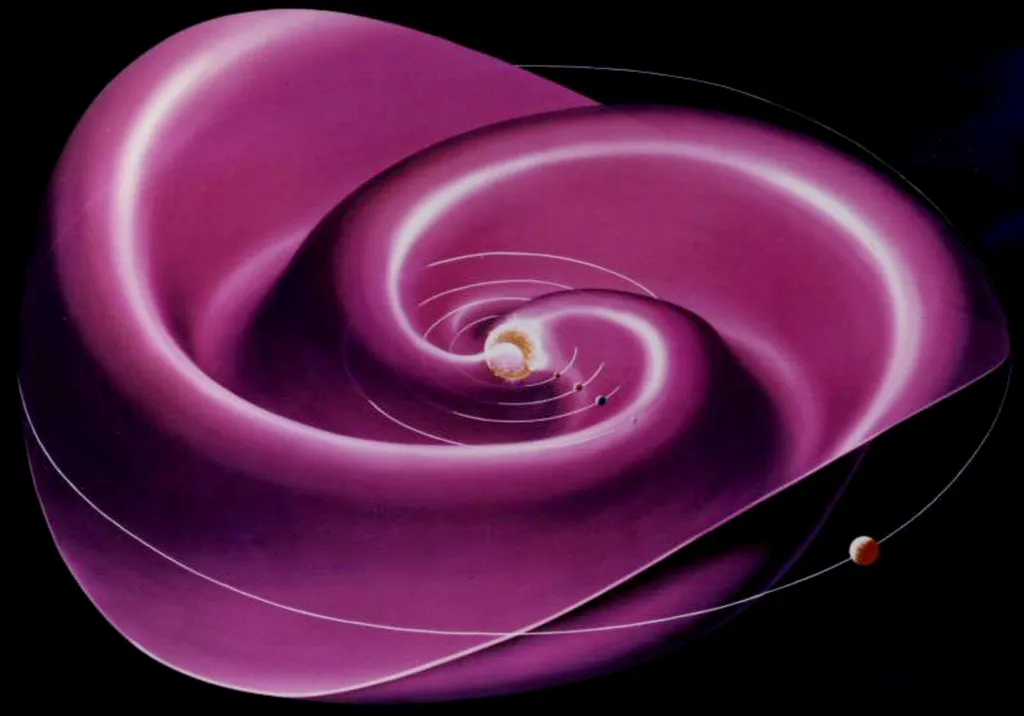

RDT occurs when gradients in the background Alfvén speed, a type of wave in magnetized plasmas, partially reflect outward-propagating Alfvén waves. These reflected waves interact and dissipate via turbulence, generating heat. Previous models of RDT assumed a radial background magnetic field. However, at greater distances from the Sun, the interplanetary magnetic field is twisted into a structure known as the Parker Spiral (PS).

In this study, Abbas and Squire generalized the RDT phenomenology to include the Parker Spiral. They used three-dimensional expanding-box magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) simulations to test their ideas and compare the resulting turbulence to the radial-background-field case.

The researchers found that the underlying RDT dynamics remain broadly similar with a Parker Spiral. However, the controlling scales change: as the azimuthal field grows, it “cuts across” perpendicularly stretched, pancake-like eddies. This results in outer scales perpendicular to the magnetic field that are much smaller than in the radial-background case.

Consequently, the outer-scale nonlinear turnover time increases more slowly with heliocentric distance in Parker Spiral geometry. This weakens the tendency for the cascade to ‘freeze’ into quasi-static, magnetically dominated structures. This allows the system to dissipate a larger fraction of the fluctuation energy as heat, also implying that the turbulence remains strongly imbalanced out to larger heliocentric distances.

The researchers complement their heating results with a detailed characterization of the turbulence, providing a set of concrete predictions for comparison with spacecraft observations. These findings could potentially improve our understanding of space weather, which is crucial for the energy sector, particularly for satellite operations and power grids.

In practical terms, a better understanding of the solar wind and its interactions with the Earth’s magnetic field could lead to improved space weather forecasting. This, in turn, could help protect energy infrastructure from the potentially devastating effects of solar storms. For instance, improved forecasting could allow for better preparation and mitigation strategies, reducing the risk of power outages and damage to satellites.

Moreover, understanding the heating mechanisms of the solar wind could also have implications for fusion energy research. The processes that heat the solar wind are similar to those that occur in fusion reactors, and studying them could provide insights into how to better control and optimize fusion reactions.

In conclusion, while this research may not directly translate into immediate energy applications, it contributes to our fundamental understanding of plasma physics and space weather. This knowledge is invaluable for the energy sector, particularly for those involved in satellite operations and power grid management. As we continue to explore and harness the power of the sun, understanding the solar wind and its interactions with the Earth’s magnetic field will be increasingly important.

This article is based on research available at arXiv.