In the realm of high-energy nuclear physics, researchers from the University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, including Lejing Zhang, Wen-Jing Xing, Shanshan Cao, and Guang-You Qin, have been delving into the intricate world of heavy-ion collisions. Their recent study, published in the journal Physical Review C, focuses on the behavior of dielectrons—pairs of electrons and their antiparticles—that originate from the decay of heavy flavor hadrons in these collisions.

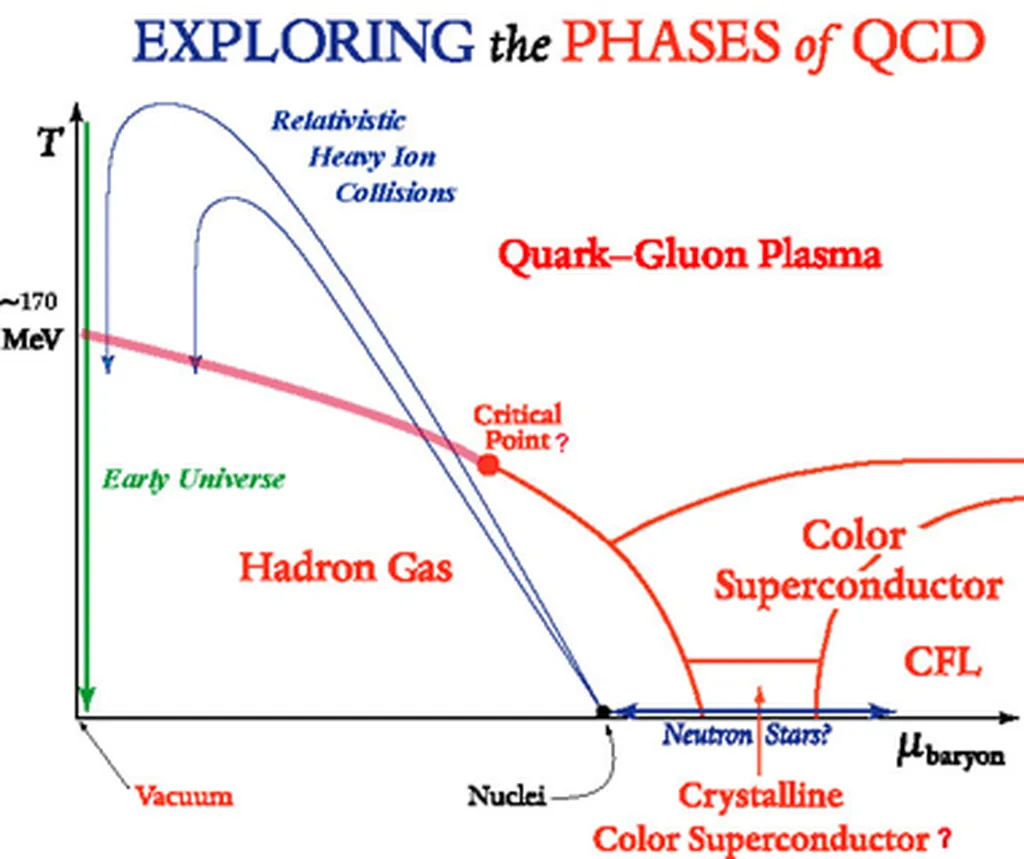

The researchers employed a sophisticated model called the linear Boltzmann transport (LBT) model to simulate the evolution of heavy quarks within the quark-gluon plasma (QGP), a state of matter that existed just after the Big Bang. They also used a hybrid fragmentation-coalescence model to describe how these heavy quarks transform into hadrons. Their findings reveal that the energy loss experienced by heavy quarks as they interact with the QGP has a significant impact on the invariant mass spectrum of the dielectrons produced from their decay. Specifically, this energy loss softens the spectrum, leading to a higher estimated temperature for the QGP.

Conversely, the process of coalescence, where heavy quarks combine with lighter ones to form hadrons, has the opposite effect. It hardens the dielectron spectrum and results in a lower estimated QGP temperature. The researchers also discovered that considering the full range of medium effects in their analysis leads to higher temperature estimates compared to using vacuum baselines—where the medium effects are not taken into account.

Furthermore, the study found that the angular correlations between dielectron pairs are sensitive to the interactions between heavy quarks and the QGP. The radial flow of the QGP enhances the near-side correlations, while scatterings between heavy quarks and the QGP broaden the away-side correlations. Elastic interactions and string interactions play a dominant role in this broadening effect.

The practical applications of this research for the energy sector are not immediate, as it primarily contributes to our fundamental understanding of the strong force and the behavior of matter under extreme conditions. However, a deeper understanding of these processes can inform the development of future technologies, such as advanced nuclear reactors or other energy systems that rely on a detailed knowledge of particle interactions. The insights gained from this study could also contribute to the development of more accurate models for simulating and predicting the behavior of complex systems, which could have broader implications for energy research and other fields.

This article is based on research available at arXiv.